At my parish , there is a caregivers group. It focuses mostly on caregiving of parents, although all are welcome. I spoke to the group on issues they face with elderly caregiving and shared some of my experiences as a person who both has a personal assistant and an aging parent.

One thing became massively clear to me: the issues concerning elder care very significantly from those facing people with disabilities who need the services of a PA. I really felt, which I relayed later on to the woman running the group, that there were others better qualified to talk about elder care. I gave her a few names of folks who work in the field.

Our social programs have tended to lump together the services for both elders and disabled folks. It is more cost effective to do so. But it’s incongruent. Services geared toward the elderly fulfill different needs than those created for people with disabilities. Our needs are different. Yet we still put seniors and the disabled together in federal housing, meal programs, transportation services and the like.

This has stalled progress in many areas for people with disabilities since, aside from the personal assistant care programs, we lack social programs designed for their needs. At present, a social worker writes down that you’re receiving services from such and such a program for seniors. Whether those services meet your needs or not, it’s on paper and that goes to decrease the hours you may receive from a PA. Worse yet, if you “complain” that the services don’t meet your needs, the pen comes out and you’re deemed “noncompliant.” The prevailing thought seems to be that you’re turning down help and assistance if you point out that the elder service organizations don’t meet your needs.

The head of one local organization run for the aged really got perturbed at me when I explained that their services didn’t match my needs. The woman began to argue with me, telling me that they “help other young people with disabilities too”. I told her that every time I asked for help, she told me it was something they didn’t do . Yet even though I received no services from them, they would call and insist I be home to accept a “senior package” which contained items for seniors or a visit or some such thing. They never came when scheduled but would call and reschedule more times that I had to be home for these things, telling me “they” were busy. Whenever this happened I would look down at my stack of work and sigh. I asked her if she could just take me off the list for the packages, etc. and she adamantly refused, saying it would cause them too much work to “treat me differently”. She just couldn’t see things from my point of view- and ended the conversation by saying I would be struck off the list if I couldn’t go along with the packages. That was fine with me! Clearly I had become the noncompliant patient to her.

There is a vast difference between a medical model of care and a consumer model, which disability advocates have fought for and incorporated in personal assistant/independent living programs. A medical model of care sees the recipient as a passive participant. Think of a nursing home situation where others run the schedule and tell the patient what his/her needs are. Compliance is the goal along with efficiency. This model is behind most elder care services to date. (I bet there are lots of seniors who don’t like it either.) They tailor their services and you receive them. You have no input into them.

In a consumer model of care which is used in the Personal Assistant Program I am in, the (disabled) consumer is empowered to direct his/her own care. There is a structure in which an evaluation is done and a task list is drawn up, but within those guidelines a consumer acts as the employer of the personal assistant and directs the care.

You can see the vast difference in these approaches. Supplementing hours to a personal assistant program with services from a medical model just doesn’t fit. There are legitimately different needs for seniors and disabled people and services designed for the elderly should not be forced upon people with disabiliities when they are inappropriate.

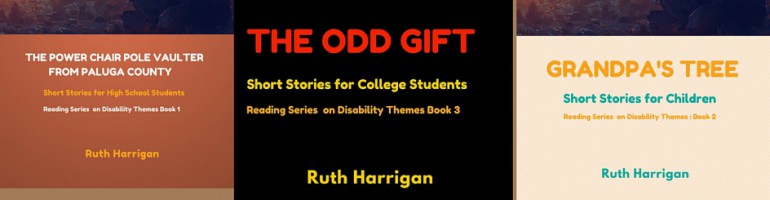

Copyright 2007 Ruth Harrigan